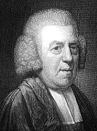

About the Author

About the Author

John Newton (1725-1807) received godly instruction from his mother as a young child, but she died when he was seven, and after the unwholesome influences of a stepmother and boarding school, he followed his father's influence and became a sailor. Onboard ship, he became an infidel of the most ungodly sort. Of his condition in those days, he writes, "My breast was filled with the most excruciating passions; eager desire, bitter rage, and black despair"; "I was capable of any thing; I had not the least fear of God before my eyes" and "I was tempted to throw myself into the sea ... But the secret hand of God restrained me." According to one biographer, "It is reported that at times he was so wretched that even his crew regarded him as little more than an animal." He fell into the hands of a slave-trader in Africa, and suffered all manner of hardships there, being continually insulted and almost starved. He survived to make several voyages to Africa in that shameful occupation of slave-trader, but after being influenced by the reading of a devotional book, followed by a "great deliverance" from a violent storm, he experienced a life-changing conversion to Christ in 1748, at the age of 23. He was ordained to the Anglican ministry about fifteen years later, but the intervening period brought intense biblical study and influential friendships with men of God such as George Whitefield and John Wesley. His 16 years as pastor at Olney brought about his longtime friendship with poet and hymnwriter William Cowper, during which Newton himself wrote the hymns for which he is most famous: "Amazing Grace," "Glorious Things of Thee are Spoken," "How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds," and nearly 300 others. When asked to give up preaching because of the infirmities of old age, he replied, "What! shall the old African blasphemer stop while he call speak?" He remained throughout his life a convinced Calvinist in his theology, and a loving shepherd of souls. Shortly before his death he said, "My memory is nearly gone, but I remember two things, that I am a great sinner, and that Christ is a great Saviour."

Messiah's Easy Yoke

A Sermon by John Newton (1725-1807),

(Author of the hymn, "Amazing Grace")

"Come to Me, all you who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take My yoke upon you and learn from Me, for I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls." (Matthew 11:29-30)

The Gospel offer in these words can only be rightly understood and valued by those who find themselves in the circumstances for which it is designed give relief. Many people may acknowledge the skill of a physician in a general sense, but his services are earnestly sought only by those who are sick (Matthew 9:12). Our Savior’s gracious invitation to come to him for rest will be given little regard until we really feel ourselves weary and heavily burdened! This is the main reason the Gospel is heard with so much indifference, for even though sin is a great illness and a hard bondage, one effect of it is a strange dullness which makes us, like a person out of his right mind, not conscious of our true condition. It is a happy time when the Holy Spirit, by his convincing power, removes that stupor, which has prevented us from fully perceiving our misery and rendered us indifferent to the only means of deliverance. Such a conviction of the guilt and deserved consequences of sin is the first hopeful symptom for the sinner, but it is by necessity painful and distressing. It is not pleasant to be weary and heavy laden; but it awakens our attention to him who says, "Come unto me, and I will give you rest," and makes us willing to take his yoke upon us.

"Take My yoke upon you." The yoke Jesus is speaking of refers to what is placed on an animal to make it useful in service to man. Our Lord seems to use it here to refer both to our required service to God, as well as to our natural prejudices against it. Though he himself submitted to sufferings, reproach, and death for our sakes, he invites us to come, not because he has need of us, but because we have need of him, and cannot be happy without him!

Yet our ungrateful hearts think unkindly of him. We conceive of him as a hard master; and suppose that, if we engage ourselves to him, we must say goodbye to pleasure, and live under a continual restraint. We consider his rule too strict, his laws too severe; and we imagine that we could be happier following our own plans than by following his. Such unfair and dishonorable thoughts of him whose heart is full of tenderness, whose heart melts with love, are strong proofs of our moral corruptness, blindness, and depravity; yet still he continues his invitation, "Come to me." It is as if he had said, do not afraid of me; only prove me, and you will find that what you have considered my "yoke" is really true liberty; and that in my service, which you have avoided as burdensome, there is no burden at all; for "my ways are ways of pleasantness, and all my paths are peace."

I have a good hope, which many of my hearers can testify from their own happy experience, that in His service is perfect freedom. If we are really Christians, Jesus is our Master, our Lord, and we are his servants. It is in vain to call him "Lord, Lord" (Luke 6:46), unless we keep his commandments. They who know him will love him; and they who love him will desire to please him, not by a course of service of their own devising, but by accepting his will, as it is revealed in Scripture, as our standard and rule of life.

"And learn from Me." He is our Master in another sense: he is our great Teacher, and if we submit to him as such, we are his "disciples" or "scholars." We cannot serve him acceptably unless we are taught by him. The philosophers of ancient times had their disciples, who followed their teachings, and were therefore called after their names, such as the Pythagoreans who followed Pythagoras, the Platonists who followed Plato, and so on. The name "Christians," which was first used of the believers at Antioch (Acts 11:26) (possibly by divine direction), suggests that they are the professed disciples of Christ. If we wish to be truly wise, wise unto salvation, we must apply ourselves to him, for in this sense, the "disciple" or "scholar" cannot be above his Master (Luke 6:40). No earthly teacher is so thoroughly learned, or so free from mistake, as to deserve our total confidence. But they whom Christ condescends to teach shall learn what no human instruction can teach. Let us consider the peculiar, unspeakable advantages of being his disciples:

First, this great Teacher can give us the ability to receive his divine instructions. This is not true of any other teacher or subject, for not one can excel in human arts and sciences, without some natural ability in the subject. But Jesus can open and make alive the dullest mind; he teaches the blind to see, and the deaf to hear. By nature we are stubborn and incapable of loving divine truth, but he takes away the heart of stone, enlightens the darkest understanding, and inspires a taste for the sublime lessons he proposes to them. In this respect, as in every other, there is none who teaches like him (Job 36:22).

Second, he teaches the most important things. The subjects of human science are comparatively trivial and insignificant. Experience and observation abundantly confirm Solomon's remark that "he who increases knowledge increases sorrow: the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear with hearing" (Ecclesiastes 1:8-18). Unless the heart is seasoned and sanctified by grace, the sum total of all other learning is nothing but "vanity and grasping for the wind" (Ecclesiastes 2:17). Human learning will neither uplift the mind under trials, nor weaken its attachment to worldly things, nor control its impetuous passions, nor overcome the fear of death. The confession of the learned Grotius, towards the close of a life spent in literary pursuits, was "Alas! I have wasted my whole life in taking much pains to no purpose." But Jesus makes his scholars wise unto eternal life, and reveals knowledge to people of weak abilities, or, as Jesus called them, "infants" (Matthew 11:25), which no wisdom of this world can do.

Third, other teachers can only inform the head, but Jesus' teaching influences the heart. The philosophers may abound in fine words concerning the beauty of virtue, fairness, benevolence, and equity; and their scholars learn to talk after them. But their fine and admired words are mere empty notions, destitute of life and power, and frequently leave their followers under the tyranny of pride and the same vices that afflict the "unenlightened" ones whom they despise for their ignorance. But Jesus Christ effectually teaches his true disciples, however imperfect they may be, to hate and forsake evil and impurity, and inspires them with love, power, and a sound mind. Their lives are exemplary and useful, their deaths are comfortable, and their memory is precious.

Fourth, the disciples of Jesus are always learning. The incidents of human life, the people we know, the conversation we hear, the unexpected events that take place in families, cities, and nations, provide a continuing commentary on what the Scriptures teach concerning the heart of man and the state of the world, as dominated by human pride and vanity, and lying in wickedness. By these lessons, the great truths we are to learn and remember are repeatedly and forcibly exhibited before our eyes, and brought home to our hearts. It is the peculiar advantage of the Jesus' disciples that their lessons are always before them, and their master always with them.

Fifth, this teacher is not wearied by his disciples' weakness and dullness. He is pleased to say, "Learn of me, for I am meek and lowly." With what meekness did he converse among his disciples while he was with them upon earth! He allowed them, at all times, a gracious freedom of access. He bore with their mistakes, reproved and corrected them with the greatest mildness, and taught them as they were able to bear, leading them on, step by step, and waiting for the proper season of unfolding to them those more difficult truths, which at times appeared to them to be "hard sayings" (John 6:60). And though he is now exalted upon his glorious throne and clothed with majesty, still his heart is made of tenderness, and his compassions are still abundant! We are still directed to think of him not as one who cannot be touched with an understanding of our weaknesses, but as having the same patience and sympathy towards his disciples now as he did during his state of humiliation on earth. If we properly consider his greatness alone, it seems presumptuous in creatures like us to dare take his holy name on our polluted lips; but if we understand his unbounded goodness and grace, every difficulty is overruled, and we feel a liberty of drawing near to him, though with reverence, yet with the confidence of children when they speak to an affectionate parent.

"I am gentle and lowly in heart." There was nothing in His external appearance to intimidate the poor and the miserable from coming to him. He was lowly, or humble, words which do seem readily to apply to our great God, yet it is said of him, "He humbles himself to behold the things that are in heaven and in earth" (Psalm 113:6).

In comparison to the "high and holy One who inhabits eternity" (Isaiah 57:15), all distinctions among his creatures vanish; and he humbles himself no less to notice the worship of an angel, than the fall of a sparrow to the ground. It belonged to his dignity, as Lord of all, to look with an equal eye upon all his creatures. None could recommend themselves to him by their rank, wealth, or abilities; none were excluded from his regard because they lacked those things which are highly esteemed among men. And, to stain the pride of human glory, he was pleased to assume a humble place: "Though he was rich, he made himself poor" (2 Corinthians 8:9), for the sake of those whom he came into the world to save. In this respect he teaches us by his example: "He took upon himself the form of a servant" (Philippians 2:7), a poor and obscure man, to tear down our pride, to cure us of selfishness, and to reconcile us to the cross.

"And you will find rest for your souls." The happy effect of his instructions on those who receive them is "rest to their souls." He gives rest to our souls, (1) by restoring us to our proper place of dependence upon God, for until our wills are truly submissive to the will of God, we can have no rest; (2) by showing us the emptiness of the world and thus putting an end to our wearisome desires and pursuits after uncertain, frequently unattainable, and always unsatisfying things; (3) by giving us more wonderful pleasures and hopes than this present state of things can possibly give; and (4) by furnishing us with those helps and encouragements that make our duty to him desirable, practicable, and pleasant. How true, then, is Jesus' promise in this passage! Only those who have tasted of it can rightly judge its value, and can rightly compare it to the miseries, regrets and fears of those who live without God in the world!

Many hearing my words already claim to be his followers. If that is the case, should we not seriously ask ourselves what we have actually learned from him? Surely the proud, the pleasure-seeker, and the worldly, though they have professed his name, and may have attended his gatherings of his church and other external things, have not sat at his feet, or partaken of his spirit. It does not requires a long period of self-examination to determine whether you have entered into his rest or not, and if you have not yet attained it, whether you are seeking it in the ways that he requires. That rest, if you have entered it, is rest for your soul; it is a spiritual blessing, and therefore does not necessarily depend upon external circumstances. Without this rest, you would be restless and comfortless in a palace, but if you have it, you may be happy in a dungeon. Today, while it is called today, hear his voice; and while he says to you by his word, "Come to me, and learn of me," let your hearts answer, "Behold we come to you, for you are the Lord our God" (Jeremiah 3:22)!